- January 2, 2023

- No Comment

- 11 minutes read

Part 2: After being convicted of poisoning his new wife, a former … – The Morning Call

This story was first written for the Mahanoy Area Historical Society.

Second of a two-part series. Read Part 1

Convicted of poisoning his new wife, former Mahanoy City druggist Robert W. Taylor sat in Schuylkill County Prison, facing more than seven years in solitary confinement.

The 36-year-old, who had escaped from Berks County Prison after a burglary conviction nine years earlier, was defiant during the trial in January 1901 and the sentencing the next month. He broke out in March.

“WALLS STAND NOT IN WAY OF BOB TAYLOR’S ESCAPE,” The Pottsville Daily Republican headline read.

The newspaper described Taylor as an “expert pharmacist and ingenious convict.”

Taylor dug a hole in the cell wall with an iron bar from the kitchen or washhouse. He climbed over the prison wall, using a 23-foot rope made from bedding with an iron hook fastened to one end. A night watchman saw him on top of the 20-foot wall and fired shots at him, but Taylor was gone. His golden spectacles were found outside the prison wall.

News of Taylor’s escape drew crowds at the prison eager to see Cell No. 12. The hole in Taylor’s cell was 20 inches long, 9 inches deep and 14 inches wide. Warden Edwin K. Barto suspected Taylor had help.

Taylor was considered the most desperate and dangerous inmate in Schuylkill County. Not long before his escape, Taylor told Barto that he would kill him if necessary to escape.

In addition to poisoning his wife, who survived, he stood accused in the suspected poisoning death of his 14-year-old stepdaughter, Elsie Myers. She and her mother both drank from the same glass of tainted water in the drug store. Taylor had been hired by Myers in late 1899 to manage her deceased husband’s drug store. They married in September 1900.

At the time of his escape, Taylor was described as having a ruddy complexion, brownish hair, blue eyes, red, sandy, stubby whiskers, a scar on the left side of his face, 5 feet 8.5 inches tall, 160 pounds with broad shoulders and nearsighted.

Taylor was caught the same day in Reading in a coal train caboose. He had boarded near Port Clinton. A flagman recognized him and telegraphed to Reading. Officers were waiting when the train arrived.

Taylor had a red bandana tied around his head and over his left eye. He was lame in one foot from his fall from the prison wall.

A physical wreck, he arrived back at the Schuylkill County Prison the morning of March 21. More than 1,000 people gathered at the Pottsville station to see him. Another crowd gathered at the prison. When Taylor got off the train with Chief Hiram S. Davies, he limped badly.

“On a pallet of straw, in a dark corner of Cell No. 17, lies the emaciated form of Robert W. Taylor, the linguist, scholar and savant,” The Pottsville Daily Republican wrote.

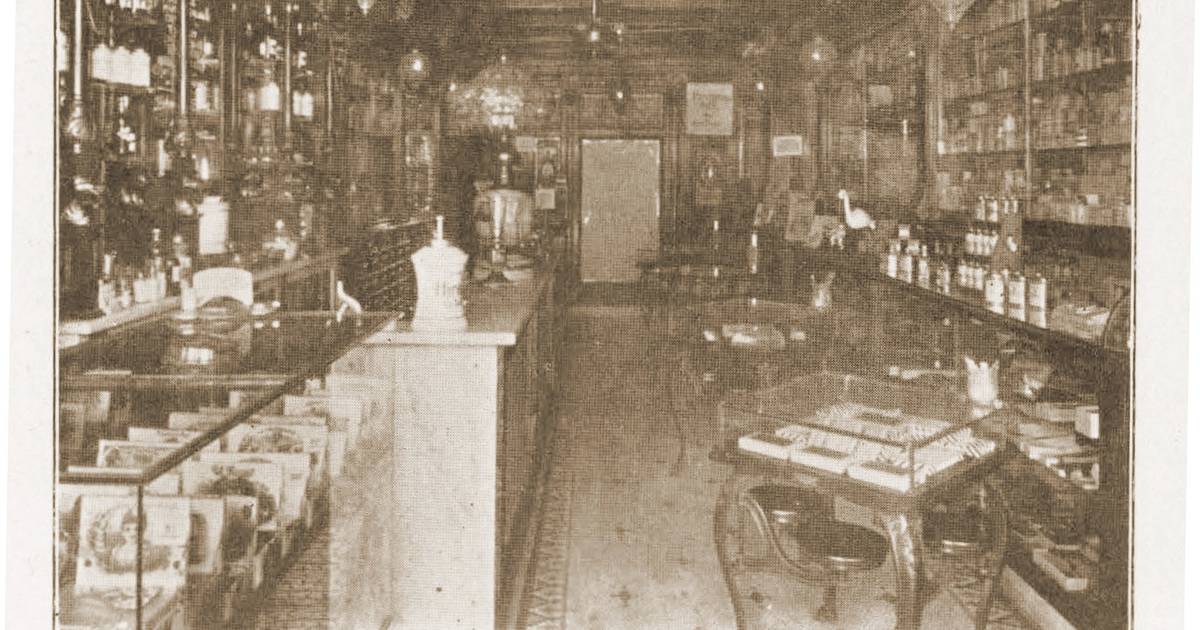

Robert W. Taylor, druggist, convict and prison escapee, is shown far left, in front of what is now known as A.G. Timm’s Drug Store on Centre Street in Mahanoy City, where he worked. (COURTESY OF DOUGLAS K. LAWSON / XX)

A prisoner suspected of helping Taylor escape was held longer than his sentence but was not charged.

On April 1, 1901, the court granted Mary Myers’ divorce, allowing her to testify against Taylor in Elsie’s death. However, District Attorney Michael P. McLoughlin wouldn’t say if Taylor would be indicted for Elsie’s murder. The newspaper said there was no time limit and authorities were being careful to avoid legal technicalities. On April 24, the prosecuting attorney said it was unlikely an indictment for murder would be presented to the grand jury in May.

Taylor never faced trial in Elsie’s death. The Miners Journal reported in 1906 that Taylor had been charged with poisoning Elsie, but the indictment was later dropped. No news articles were found stating when or why that occurred. It’s likely the experts’ refusal to swear the girl died from poisoning was a factor.

In his last public appearance in Schuylkill County, Taylor pleaded guilty to jailbreaking and received one more year and nine months in addition to his previous sentence. On May 10, 1901, Taylor was sent to the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia for his remaining term.

On Oct. 4, 1906, the Eastern State Penitentiary prepared to release Taylor early because of his “good behavior.” The date of his release was not reported.

On Nov. 16, Taylor wrote a letter to The Pottsville Daily Republican that filled almost five columns.

Taylor again claimed his innocence. He referred to himself in the third person and cast suspicion on his ex-wife, Mary Myers. He wrote that he did not find it plausible that “two sane people would drink alternately out of the same glass, several ounces of tepid gallish water, not for medicinal purposes but as a cooling beverage.

“Would anyone marry for love or money and inside of ten days want a divorce, or would anyone, with sufficient matter in their cranium to keep a firefly going, awaken his victim and send thrice for a doctor if his motive was homicide?”

“In conclusion, I reiterate the assertion of the victim, Taylor’s innocence and that this toxic potion was intended for his riddance.”

A few months later, on March 1, 1907, Taylor was charged with two counts of selling liquor without a license in Shippensburg. He was working as a clerk at a drug store he bought intending to go into business.

He was held on $500 bail in each case. However, Taylor escaped from a constable who was escorting him to a temporary lockup, fleeing on a team of stolen horses.

Three days later, a fire erupted in the Farmers and Drovers Hotel stables in Carlisle. Four horses got out, and a hunting dog died. Days before, Taylor had taken the stolen horses to that stable. Police believe he may have gone to the second story of the stable to hide and may have lit a match to find his way down the steps, falling in the hay, or he may have intentionally set the fire.

Taylor fled on one of the horses, which probably had been overcome with smoke and wasn’t making much progress. It was found dead, and Taylor was suspected of cutting its throat.

Police arrested Taylor at 5:15 p.m. March 5 on a Carlisle street. He had a revolver, cartridges, a razor and two knives. He was charged with arson, larceny of a horse, cruelty to animals and carrying concealed deadly weapons. He also was to face charges of selling liquor without a license, resisting an officer and larceny in Shippensburg.

On May 15, Taylor was found guilty. He was sentenced to 18 years in Eastern State Penitentiary and another year after that term in Cumberland County jail.

A lawyer for Taylor’s sister, Salina Taylor Mitchell, asked the court in May 1907 for a commission of lunacy. The petition stated that Taylor was insane because of a severe head injury when he was a child that impaired his eyesight.

“He exhibits evidence of mental derangement shown in delusions of persecution; a delusion that he is being poisoned; that his best friends are conspiring to injure him; that he has periods of excitement; becomes entirely irrational; has no recollection of recent events; lacks sufficient will power to control powerful impulses to move him to commit irrational acts, and that the recent offenses are the result of insane impulses.” The petition stated the welfare of Taylor and others required his restraint.

On June 7, 1907, the court dismissed the application. At some point after that, Taylor was transferred from Eastern State Penitentiary to the State Insane Asylum at Norristown, according to The Pottsville Daily Republican. No articles were found explaining what spurred the move.

On Aug. 28, 1910, Taylor escaped the Norristown asylum but was caught within an hour. Taylor would try again.

About 6 a.m. Dec. 26, when the iron bars of the asylum’s windows were cold, he hit them with a chain, snapping the iron. He crawled through the opening, hung on the windowsill, and dropped 25 feet to freedom.

A Reading Times story Jan. 12, 1911, reported Taylor had been captured in Washington, D.C., and an attendant was sent to bring him back. But an April 19 story that year in The Pottsville Daily Republican said he remained at large, disappearing before he could be taken into custody.

Where Robert Taylor lived and died after his final escape is unknown. The family home on North Ninth Street in Reading, known as the “house of mystery” and the “spook house” because of Taylor’s notoriety, was demolished in 1921. It had been neglected for more than two decades.

“Bob Taylor formerly lived there,” The Reading Times said in 1911. “He was an exceedingly bright lad and came from an excellent family. He went bad. Through his shortcomings, his family stood by him to the end.”

In 1927, Mary Myers died at age 72 in Mahanoy City and was buried with her first husband and daughter Elsie in Myerstown. Myers’ drug store eventually became Timm’s Pharmacy, which still stands today at 22 W. Centre St., the current CJ’s Dog House eatery.

Taylor’s mother’s obituary in 1912 didn’t list Robert as a survivor. But his brother John’s death notice in 1918 — if accurate — may hold a clue to how long Robert lived. The notice in the July edition of the Typographical Journal, the printer’s trade publication, states his entire family, consisting of his widow, two daughters, one son and a brother, attended the interment in Colorado Springs, Colorado. John Taylor Jr., who died May 21, 1918, in Iowa, only had one brother — Robert.

As for young Elsie Myers, we will never know for sure if her stepfather poisoned her.

Missed Part 1? Read it here: An eastern Pennsylvania mystery: Was 14-year-old girl murdered by her stepfather?

Terry Rang, former editor-in-chief of The Morning Call, wrote this article for the Mahanoy Area Historical Society. The society’s historian, Paul Coombe, provided research. Go to mahanoyhistory.org for more information about this story and the society.

Newspapers and other sources used in this reporting include The Pottsville Daily Republican, The Evening Herald, The Miners Journal, the Reading Times, the Carlisle Sentinel and The Philadelphia Inquirer. Other sources included the U.S. Census and other public records.

Copyright © 2022, The Morning Call

Copyright © 2022, The Morning Call