- September 20, 2022

- No Comment

- 13 minutes read

Lake City seeks investments from Seattle City Hall amid growth, change – The Seattle Times

Much of the stream called Little Brook flows below the pavement in Seattle’s Lake City neighborhood, emerging for just a moment to burble through a small park shadowed by apartment buildings.

For some people living near Little Brook Park, the almost-hidden stream is a metaphor for the surrounding area: Unjustly overlooked, with a beauty that runs deep. There are plans to renovate the park to better accommodate the diverse and growing neighborhood, with funding needed.

“It’s the only access to nature that this community has,” said César García, co-director of Lake City Collective, an advocacy group that focuses on people of color. “There cannot be equity [among Seattle parks] until that park gets redeveloped.”

As Seattle leaders weigh competing demands for precious public dollars this month, considering a proposal to boost property taxes by more than $50 million annually to address parks and recreation needs, few neighborhoods have as much at stake as Lake City, which has been waiting years for a new community center, as well.

Roughly one mile south of Little Brook Park, in Lake City’s mini-downtown, the neighborhood’s current center is one of Seattle’s most deficient. Housed in a 65-year-old building once run by a Lions Club, it has no basketball gym and scarce amenities. Volunteers who serve meals to seniors there cook at a church elsewhere, because the center’s kitchen is inadequate.

Now, the City Council is considering a proposal by Mayor Bruce Harrell to double Seattle Park District property taxes to pay for projects across the city, including a new community center with affordable apartments on top and, potentially, the redevelopment of Little Brook Park.

Those improvements wouldn’t solve all of Lake City’s challenges. Still, advocates say renovations could make Little Brook Park a sanctuary for kids. They say the new community center, planned to replace the existing center on the same site, could be a multicultural hub.

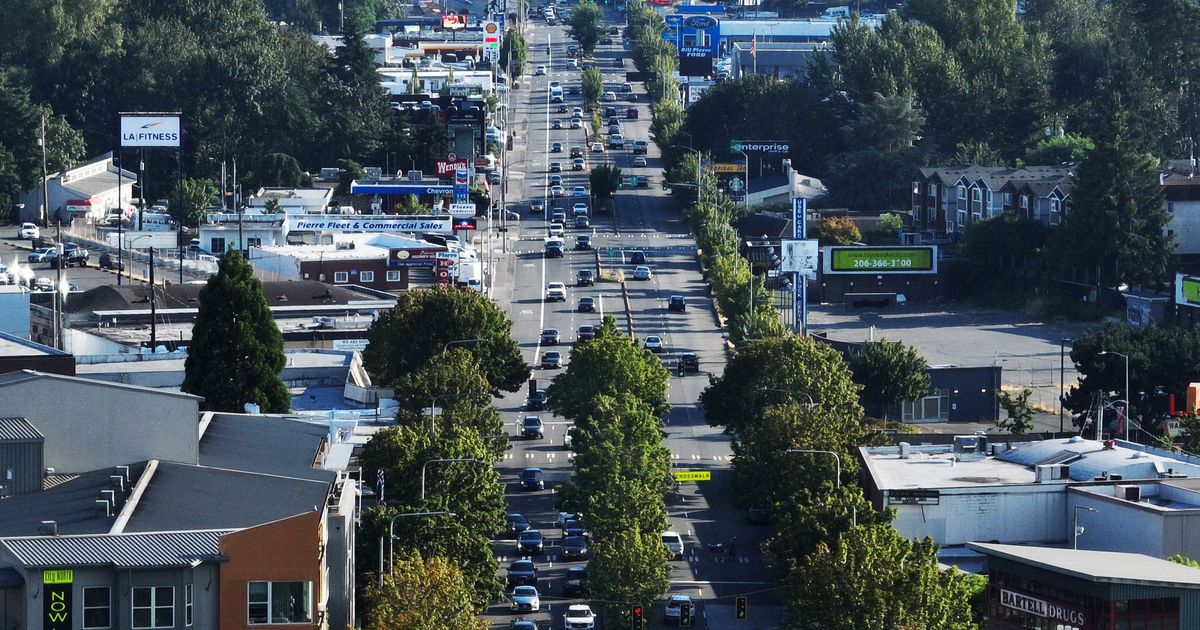

Long known for the car dealerships on its main drag, a state highway, the neighborhood has welcomed immigrants from around the world and newcomers bumped from pricier parts of Seattle. Bright murals and restaurants with globe-spanning menus line Lake City Way Northeast, and more than 2,000 additional housing units are on the way.

Judy Kuguru, who recently opened a thrift store in the neighborhood and lives nearby, imagines a new community center as a place that could host birthday parties for her daughter, meals for her mother and yoga classes for herself.

“We need this resource” as soon as possible, Kuguru said. “This is not just going to be a building. It’s going to be like a second home, a place for everybody, rich and poor, a place that equals us all out.”

The council may vote on Harrell’s Park District proposal this week.

Lake City wasn’t annexed by Seattle until 1954 and retained a suburban character for decades, with more than a dozen acres controlled by the family of the late car dealer Bill Pierre. It was designated an “urban village” by City Hall but has seen less development than areas like Ballard and South Lake Union.

Today, Lake City is among Seattle’s less expensive, more diverse neighborhoods. Its ZIP code (with Northgate) was 43% people of color in 2020, up from 34% in 2010, per census data, with a median household income about $20,000 below the city as a whole. The dense tract that includes Little Brook Park was 59% people of color.

Diana Quintero-Perez, a University of Washington student who grew up in Lake City and still lives there, has noticed changes while shopping at the local Fred Meyer store.

“Now you see a lot of people from different backgrounds,” and more products catering to Hispanic and Asian customers, said Quintero-Perez, who’s volunteered with Lake City Collective and other groups.

More changes are coming. The 2,300 apartments currently under construction or planned include rent-capped and market-rate units, said Chris Leverson, project manager for Build Lake City Together, an effort sponsored by Children’s Home Society of Washington.

Businesses could benefit from the surge bringing more customers within walking distance. Yet the boom also could contribute to displacement, Leverson said. Demolitions and rent hikes have already begun, he said, calling this a crucial “window of time” to support the neighborhood.

“These days,” said Tsegay Berhe, a leader at Lake City’s Trinity Eritrean Orthodox Church and HOPE Eritrean Social Services, “housing is the No. 1 concern” among residents who wonder whether the changes will “relieve the rent pressure” or drive costs higher.

“We worry a lot,” about having to leave, added Quintero-Perez, “because we never know how much they’re going to increase the rent,” with current residents not guaranteed spots in the new buildings.

Visible homelessness exploded in Lake City after COVID-19 hit, with tents taking over Albert Davis Park, between the community center and the Lake City library. Many people are still unsheltered.

“We’ve got a lot of folks who went to high school in Lake City,” said Kathryn Whitehill, program director at God’s Little Acre, a day center with a kitchen, laundry and showers. “We’re also seeing a lot of new faces.”

Because other North End neighborhoods are well-off, Seattle programs for disadvantaged communities tend to neglect Lake City, directing resources mostly toward the South End, Berhe said. That’s the problem, he said.

Families around Little Brook Park desperately need a place to relax, but the site has egregious flaws, García said. Some streets in the area lack sidewalks, and dog owners take their pets to the park for bathroom breaks, polluting the stream and a grass lawn enough that kids don’t use it, he said. The park has no basketball court, so kids play on a donated, portable hoop that Lake City Collective set up, and drug dealers work the vicinity, García added.

Down at the community center, the room where seniors eat lunch and practice tai chi has no windows and no air conditioning. The center is open only 25 hours weekly, with activities constrained by the structure.

The seniors’ meals are lovingly crafted, “But we have to pack everything into boxes while it gets soggy and take it on a 10-minute drive,” said Darcy Buendia, a co-executive director of the Hunger Intervention Program.

There are sparks of positive energy in Lake City, said Mark Mendez, a community leader who’s partnered with kids, artists, nonprofits and businesses to create dozens of murals since 2016.

Painted in an alley between a brewhouse and a sushi restaurant is a whimsical neighborhood scene, rendered in pink, blue, yellow and green. “This one is about protecting the ocean,” Mendez said, pointing at another wall. Down the street is a mural depicting Lake City’s history, including Indigenous ancestors, a Japanese American garden store and Dick’s Drive-In.

Residents speak 20-plus languages, and “You can travel the world in two blocks” by dining at local restaurants, added Mendez, who works at the existing community center and helped organize outdoor concerts this past summer. He argues Lake City can thrive as an arts and culture hotbed.

“I can’t paint or draw,” he said. “But I know the power of art.”

The nonprofit Coyote Central, which offers pay-what-you-can art classes to kids, opened a Lake City branch in 2020, and the Refugee Artisan Initiative, which trains immigrant women to make clothes and home goods using recycled materials, is located on the same block.

When Kuguru started working in Lake City, an acquaintance jokingly disparaged the neighborhood. That bothered the Thriftology owner, who sees “so much” that the area offers.

Families hang out at the Refugee Artisan Initiative workshop; Build Lake City Together has opened a temporary arts and culture center in a onetime pawnshop; and Children’s Home Society of Washington plans to open a community venue next year.

Up in the Little Brook area, Lake City Collective has opened a gathering space called the qʷiʔqʷuʔ Center (pronounced “kwai quo,” meaning “little water” in Lushootseed) in a building that faces a school bus parking lot. Previously, residents met in Little Brook Park, with cars whizzing by. The city recently closed the block to vehicles via the Stay Healthy Streets program, thanks to advocacy by Lake City Collective, which now holds events between painted planter boxes.

Kids play there and “We just had lucha libre” Mexican wrestling, García said.

City Council President Debora Juarez, who lives in Lake City and represents the North End, said it’s gained attention since 2015, when the council moved to district seats.

The library was remodeled; low-income apartments with a preschool have been added; and a new pocket park and a Seattle Indian Health Board clinic are opening, among other steps. Juarez has lobbied for the new community center, she said.

“These projects … we’ve been peeling them away, one by one,” she added.

Little Brook Park hasn’t been peeled away yet. Lake City Collective got help from the Seattle Parks Foundation last year to redesign it, based on input from residents. The cost estimate is about $2 million, with possibilities including a basketball court, spray park and dog zone, García said.

Harrell’s Park District proposal includes a new equity fund, with Little Brook Park on a list of projects likely to benefit. The park is García’s priority, above a new Lake City Community Center, because the Little Brook area is geographically isolated and gets excluded from decision-making, he said.

“The problem is who is deciding what’s best for the neighborhood,” García said, wondering why the current concept calls for housing with the community center but no swimming pool.

Muriel Lawty, a resident active with the Lake City Neighborhood Alliance, has been pressing for details about the long-sought new center, which has $11.5 million earmarked already (real estate taxes and a state grant).

“A lot of us have been wondering what’s going on,” Lawty said.

Under Harrell’s proposal, the city would issue a $28 million bond for the new center and use about $2 million in Park District taxes each year to gradually repay the debt. The Parks Department has countless needs across Seattle, from restroom access to graffiti removal, but Lake City deserves a larger, modern center and the site presents a “unique opportunity” to also build affordable housing, said David Graves, a department adviser.

A 2018 feasibility study suggested a new building might include five levels of housing above a two-level center with a gym, activity rooms, child care space and a commercial kitchen.

The housing, which would require separate financing, has added “a huge wrinkle” to the planning process, with COVID-19 also causing delays, Graves said. Seattle has never built a center with apartments on city land before.

A preliminary timeline calls for the city to collect neighborhood input this winter, partner with a housing developer next spring, work on designs and permits through 2024, break ground in 2025 and open the new center in 2026. For the project to be worthwhile, that process must be inclusive and the center must serve immigrant groups better, Berhe said.

Sean Watts, an environmental justice consultant who worked on Lake City issues from 2016 to 2018, is disappointed City Hall didn’t pursue an ambitious idea to replace an adjacent block of businesses with a new community center and housing, orienting them and the library around a green plaza.

Even so, Alex Eaglespeaker is anxious to see a new center built. The supermarket worker, who helped Mendez with murals during high school, said teenagers in particular need a safe place to hang out.

“We need action” from the city, he said. “We try to keep up the positivity, but at the same time, there’s only so much we can do.”

This coverage is partially underwritten by Microsoft Philanthropies. The Seattle Times maintains editorial control over this and all its coverage.

The opinions expressed in reader comments are those of the author only and do not reflect the opinions of The Seattle Times.