- July 17, 2022

- No Comment

- 8 minutes read

Boris, Brexit, and a Brit in the 'Burgh – PGH City Paper

By Jamie Wiggan

The last time I cast a vote in the UK was on June 23, 2016. Before turning in for an early night, I watched a major figurehead for the Brexit campaign concede to likely defeat on national news and drifted into an easy slumber. Jetlag roused me a few hours later, so I reached for my phone and watched as precinct after precinct instead confirmed our departure from Europe.

Before noon, prime minister David Cameron had resigned, triggering a tragicomical leadership contest that left then-future-now-former prime minister Boris Johnson among the backstabbed victims. (More to follow.)

Five months later, I was back at my new home in the states, and was, along with the rest of the country, swept up in the unfolding presidential contest between a sane but uninspiring career politician and a dyspeptic media personality promising walls, coal, and steel. This time I stayed up purposefully to follow the results, and the creeping disgust felt familiar as early wins for Trump in Ohio and Florida were followed by further gains in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, clenching him the presidency.

The unexpected rightward surge reflected by both elections signaled new political dawns in each of the countries where I now staked a claim.

Back in the UK, Johnson didn’t return to the political fore until 2019, when he again ran for the Conservative Party leadership post and this time won. (Unlike the American presidential system, the prime minister is simply the leader of the ruling party in parliament, and can change at any time outside of a general election.)

Three years on from the referendum, the British government had failed repeatedly to sell parliament on their EU withdrawal terms, forcing Johnson’s predecessor Theresa May to step aside. Johnson, the consummate opportunist, sensed his time had come. The resentment he and other Brexiteers first stoked during the Vote Leave campaign had been nurtured by years of anticipated market shocks with no compensating progress on any of their — mostly fanciful — pledges. Worn down by the failure of May’s limp diplomacy, the party and country gave in to Johnson’s manic optimism.

He took his place in Downing Street — England’s equivalent to the White House — after soundly winning the leadership vote, then quickly expanded his parliamentary majority in the biggest Tory landslide since the days of Margaret Thatcher.

It took three years of deceit, scandal, and constitutional havoc to finally bring down Johnson from these giddy heights. He was hanging on by a thread when revelations emerged earlier this month that he had approved Chris Pincher to a cabinet position while aware of investigations into sexual misconduct allegations. When ministers began resigning, first in drips, then in gushes, the thread finally snapped.

Many American pundits have been quick to applaud the Conservatives for finally ousting Johnson, noting by contrast how the Republican party has stayed slavishly devoted to Trump since his chaotic departure.

It’s reassuring that some democratic functions have survived the Johnson administration, but the comparison is more an indictment of Republican degeneracy than cause to applaud their transatlantic equivalents. Most of the resignations were submitted by party leaders who stayed doggedly loyal to Johnson through scandal after scandal until they finally sensed political advantage in withdrawing their support. Several of his recent backers are now vying to be his successor.

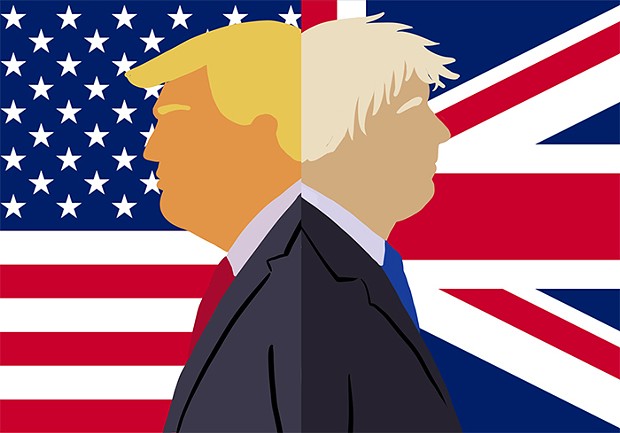

But Johnson’s demise illustrates another common shortcoming in American media analysis of the Johnson administration, namely that it represents an English equivalent of Trumpism.

The comparison has some value. Both former leaders successfully captured populist sentiments built upon declining blue-collar industries, rising immigration, and establishment support for globalization. Both carved out “man-of-the-people” profiles by eschewing political correctness and sounding dog whistles to their bases. Both won office by promising results they knew they could not deliver. More superficially, both don iconically bad bleach-blond haircuts.

Beyond these associations, though, Johnson and Trump have different political outlooks, temperaments, and backgrounds. More importantly, they operate in different political contexts.

The idea, for instance, of Johnson touring the UK after his ouster and lapping up cheers in the form of a MAGA-style rally is simply laughable. It would never happen. A prime minister is, after all, not a president. A small handful of voters from an uppity West London suburb elected him to parliament, his party peers appointed him their leader, and the rest of the country was stuck with him.

That’s not to say he was never popular. As noted, the Conservatives won their biggest parliamentary majority in 30 years from a general election held soon after his appointment, and while most of those votes were not cast for him, as party leader, he clearly pulled many along in his wake. But, ultimately, like the majority of modern prime ministers, he left office not after losing an election but by resigning at the will of his party.

A British Trump clone could not succeed in the UK, for one thing because a prime minister’s appointment by party leadership rather than through popular election — and the position’s lower stature than a presidency — discourages the rise of cult-like outsiders at odds with the political establishment. But he’d also fail in the UK because there are no equivalent movements for gun rights, banning abortion, or privatizing health care which he could mobilize for support.

BoJo and Brexit showed the UK has problems — profound ones — but they are different from those threatening America, where solutions won’t be found in the political cunning of Conservative Party ministers.

My three years in Honduras and the effects they left behind

FREE WILL ASTROLOGY: July 14-20

Growing up Black in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood

Local officials, advocates respond to death of Roe v. Wade

By Jamie Wiggan

Pa. GOP governor hopeful Mastriano campaigned at event promoting QAnon

By John L. Micek

U.S. House committee subpoenas Sen. Doug Mastriano as part of Jan. 6 investigation

By Marley Parish

Pa. court to hear arguments over releasing voters’ identifying information as part of election investigation

By Marley Parish

My three years in Honduras and the effects they left behind

By Ladimir Garcia

Growing up Black in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood

By Tereneh Idia

I don’t have a “good” abortion story. And that’s OK.

By Jessica Semler

An insider’s take on the Tito-Mecca-Zizza House landmarking

By David S. Rotenstein

How becoming a dad helped save my life after years of struggling with my mental health

By Terry Jones

Humans should act like animals: A call from, for humanity

By Tereneh Idia

My three years in Honduras and the effects they left behind

By Ladimir Garcia

FREE WILL ASTROLOGY: July 14-20

By Rob Brezsny

Growing up Black in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood

By Tereneh Idia

I don’t have a “good” abortion story. And that’s OK.

By Jessica Semler