- October 29, 2022

- No Comment

- 19 minutes read

As TV doctor, Mehmet Oz provided platform for questionable products and views – The Washington Post

Sign in

Mehmet Oz looked directly into the camera and introduced his daytime television viewers to a “controversial” weight-loss approach: taking a hormone that women produce during pregnancy combined with a diet of 500 calories a day.

“Does it really work? Is it safe? Is it a miracle? Or is it hype?” he asked in a 2011 episode of “The Dr. Oz Show” before introducing his audience to “human chorionic gonadotropin,” or HCG, and to a weight-loss doctor who promoted it.

In fact, there was little uncertain about the HCG Diet. Numerous studies conducted years before Oz’s show had shown that the fertility drug does not cause weight loss, redistribute fat or suppress hunger. Ten months later, the Food and Drug Administration warned seven companies marketing HCG products that they were violating the law by making such claims, and the agency issued additional warnings to consumers in subsequent years. Nevertheless, Oz revisited the topic in 2012, providing a platform for the same weight-loss doctor, who claimed that HCG worked.

Now as a Republican candidate for a U.S. Senate seat in Pennsylvania, a key battleground in the fight for control of the upper chamber of Congress, Oz, a cardiothoracic surgeon, is putting his medical background and his popular TV show at the center of his campaign pitch. At a recent town hall in a Philadelphia suburb, he said his approaches to medicine and politics are similar: “If you teach people on television or whatever forum you use, they actually begin to use the information and they begin to change what they do in their lives. I want to do the same thing as your senator. Empower you.”

But during the show’s run from 2009 to 2021, Oz provided a platform for potentially dangerous products and fringe viewpoints, aimed at millions of viewers, according to medical experts, public health organizations and federal health guidance. Among the treatments that Oz promoted were HCG, garcinia cambogia — an herbal weight-loss product the FDA has said can cause liver damage — and selenium — a trace mineral needed for normal body functioning — for cancer prevention.

“He spouts unproven treatments for things and supposed ways to maintain and regain health,” said Henry I. Miller, one of 10 physicians who in 2015 tried to have Oz removed from the faculty at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Miller described Oz, in his view, as someone who has been an advocate of “quack cures.”

Oz and his defenders have said that his approach on the program was to give viewers hope and provide different points of view. While Oz has been criticized for promoting problematic medical claims, he also received some praise over the years for raising awareness about preventive health. He’s been bolstered by high-profile guests who appeared on his daytime show, including Oprah Winfrey — who had him as a health expert on her show before producing “The Dr. Oz Show” in 2009 — then-first lady Michelle Obama, and former Newark mayor and now-Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.).

The Oz campaign declined a request for an interview with the candidate. After The Washington Post submitted detailed questions in an email, a campaign representative sent back broad statements addressing attacks from his Democratic rival, John Fetterman; his career; and products promoted on his program, but leaving many specific inquiries unaddressed.

“On his show, Dr. Oz welcomed open, honest conversations and opinions from all kinds of folks,” said Brittany Yanick, a spokeswoman for the Oz campaign. “It’s idiotic and preposterous to imply that he shared the same beliefs and opinions as every guest on his show, or that having someone on his show constitutes a blanket endorsement of their beliefs.”

Oz did often present caveats to the treatments he spotlighted on his program. During the initial HCG episode, he told his viewers not to eat fewer than 1,200 calories a day “without a doctor getting involved,” and to avoid over-the-counter versions of the product that might be adulterated.

Pieter Cohen, who appeared as an anti-HCG expert on that episode, warned of the possible life-threatening risks of the diet and noted that research showed the injections were no better than a placebo in numerous studies. Oz concluded that there was no proof HCG had worked in the past, but with a doctor’s help, he told viewers, “I think it’s worth trying it.” And more research might give millions struggling to lose weight “an option,” he said.

Cohen, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and expert on dietary supplements, said that Oz used his reputation as an elite physician to undermine trust in legitimate medical practice.

“What’s really sad about the situation is how he used all that prestige and authority to then lead people down a path of nonsense,” Cohen said. “It undermines all of us, all of us trying to be credible physicians, doing the right thing.”

HCG and severe food restriction can be dangerous themselves, the FDA said. The agency said in late 2011, when it issued the warning letters between the two Oz episodes on HCG, that it had received reports of blood clots in the lungs, cardiac arrest and death among people who injected themselves with HCG.

Oz earned his undergraduate degree from Harvard University and his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He trained in surgery at Columbia. Yet his show often strayed to the outer edges of nontraditional health practices. He has hosted psychics and a proponent of “iridology,” the belief that examining patterns in the iris yields diagnoses for any part of the body.

The Republican Senate nominee’s television work is now a target of Fetterman, whose campaign has organized “Real Doctors Against Oz,” a collection of more than 100 Pennsylvania physicians who have railed against Oz’s past medical advice. A recent TV ad from the Fetterman campaign shows Oz hyping “miracle” supplements, including one he called “fairy dust for your belly.” “Too bad there’s no miracle cure for being a total fraud,” Fetterman tweeted with the video.

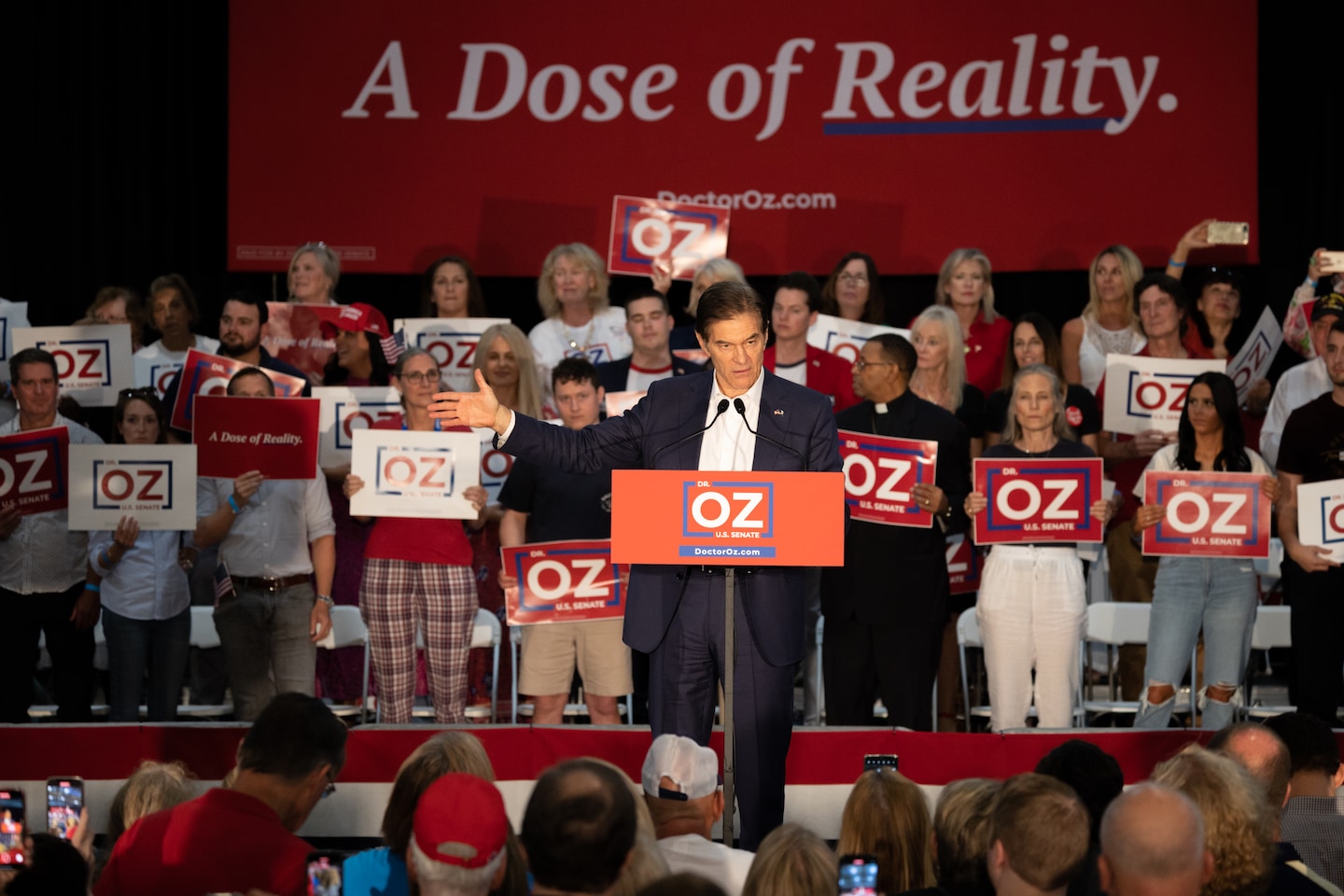

Oz’s pivot from TV celebrity to political candidate is filled with reminders of his prior job and TV show. At his events, he stands in front of banners emblazoned with “Dr. Oz” and his campaign slogan, “Dose of Reality.” He has also used the theme “The Doctor is In.” His voter town halls are situated like his TV set, with an audience surrounding him as he works the room with a microphone.

When a team of Canadian researchers examined episodes of his show in 2014, they found “believable or somewhat believable” evidence for just 33 percent of the 80 recommendations and claims they randomly selected and then reviewed. When evidence was defined as “at least a case study or better,” a low standard, it supported 46 percent of Oz’s recommendations, contradicted 15 percent and was not found for 39 percent, they wrote in the British Medical Journal. Some reviewers have challenged the way the study was conducted, and Yanick, the Oz campaign spokeswoman, pointed to criticism of it.

One of the lead researchers on that observational study, James McCormack, a professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the University of British Columbia, noted that not all medical advice from doctors rests on tested science. “Consumers should be skeptical about any recommendations [from] pretty much any televised medical talk show,” McCormack said in an interview. “Dr. Oz had lower percentages. But where do you draw that line?”

Full episodes of Oz’s show are difficult to find online. Some sites with links to episodes of his program redirect to his campaign website. The Post reviewed clips of episodes, often uploaded to sites such as YouTube and Vimeo by supplement companies for use in promoting their products, and then compared them to transcripts. The clips showed that Oz frequently spoke in animated tones and the program sometimes had the feel of an infomercial.

“Everybody wants to know: What’s the newest, fastest fat buster? You’ve been stopping me on the street, emailing me. Even my family’s asking the same question. How can I burn fat without spending every waking moment exercising and dieting?” Oz said in one episode before introducing viewers to garcinia cambogia. “Well, thanks to brand-new scientific research, I can tell you about a revolutionary fat buster. You heard it here first.”

Steven J. Dell, an eye surgeon in Austin and former president of the American-European Congress of Ophthalmic Surgery, first looked into Oz’s show after a patient mentioned coming across a mention of Oz hosting an iridologist. Dell said he began to watch and read about the man he knew as a brilliant surgeon and found a steady stream of troubling ideas.

He wrote an opinion paper for a newsletter where he was chief medical editor that claimed: “Although the scientific community has turned against Oz, the unfortunate reality is that he is perceived as a scientific authority by millions of people who receive their relationship advice from Dr. Phil and, presumably, their time-traveling advice from Dr. Who.”

“I think it’s pretty clear we don’t have definitive evidence for every single thing we do in medicine,” Dell said in an interview. “But that doesn’t mean we should believe in … taking magic potions that have been shown to contain nothing but water.”

Republicans in the state dismissed concerns that Oz’s reputation would damage his standing with voters. Charlie Gerow, a longtime Pennsylvania GOP consultant, said he hasn’t heard anyone mention Oz’s show as a factor. “The celebrity is a big plus; they know who he is. That’s very important,” Gerow said.

Public polls suggest there has been some skepticism about Oz’s authenticity. A CBS News/YouGov survey released in mid-September found 29 percent of Pennsylvania voters said they think Oz says what he really believes and 71 percent said they feel that Oz says what he thinks voters want to hear.

Oz has been sued in his roles as medical practitioner and television host, but a search of public records did not show large judgments against him. By the time a California judge approved a $625,000 settlement in July to end six years of class-action litigation over the alleged fat-busting powers of garcinia cambogia and green coffee bean extract, Oz and his production companies were no longer defendants.

A 2015 Federal Trade Commission settlement collected $9 million from a seller of green coffee bean extract for false advertising. The lawsuit said the company took advantage of appearances on the Oz show and Oz’s enormous popularity — the so-called “Oz effect” — but Oz and his companies were not defendants.

“You may think magic is make-believe, but this little bean has scientists saying they found that magic weight-loss cure for every body type: It’s green coffee beans. And when turned into a supplement, this miracle pill can burn fat fast for anyone who wants to lose weight,” Oz said on his show in 2012, according to online clips. “This is very exciting, and it’s breaking news.”

Under the heading “Supplements and products Dr. Oz promoted on his show,” Yanick, the Oz campaign spokeswoman, said in an email that “Oz discussed the scientific studies and research around these supplements after vetting by his show’s medical unit.” After mentioning in her emailed response to The Post a retracted study on green coffee bean pills, Yanick added, “Dr. Oz never sold these weight-loss products himself.”

Oz promoted more than weight-loss promises on his show. He also offered frequent unproven and, in several cases, debunked solutions for dire health circumstances, such as cancer and Alzheimer’s, as well as providing a platform for people to discuss the discredited conspiracy theory that vaccines cause autism. In 2015, Oz tweeted, “Just a reminder: there is no evidence that there is any link between vaccines and autism,” after a Republican presidential debate in which then-presidential candidate Donald Trump suggested there was a correlation between the two.

In 2011, Oz claimed a diet of “endive, red onion, and sea bass” could decrease ovarian cancer by up to 75 percent, suggesting people have the “power of prevention in their grocery cart.”

“What I love that you’ve been able to accomplish is you move past the oranges-are-good-for-you stage to, specifically, this is how they work to kill off cancer cells, just the way chemotherapy can,” Oz said. “For the first time ever, we’re going to talk about some cutting-edge foods that work and why they work.”

The Ovarian Cancer National Alliance challenged that claim, and after reviewing the studies the Oz producers used, the organization determined the data was “not strong enough to support the claims made on the program.” In 2014, researchers published an article in a peer-reviewed medical journal, Nutrition and Cancer, that critically revisited Oz’s promotion of “anti-ovarian cancer” foods, concluding there is no evidence that any one food can reduce cancer risk.

“While perhaps not as ‘sexy’ as Dr. Oz would like, the public needs more information about the effects of diet as a whole on cancer risk, as well as the importance of achieving and maintaining an ideal body weight, regular physical activity, and avoiding a sedentary lifestyle,” the researchers wrote.

Oz also promoted selenium supplements — a mineral found in foods such as Brazil nuts — in 2012, calling them the “holy grail of cancer prevention.” Several medical reviews, including by the National Institutes of Health, said there’s no evidence that selenium could stop cancer. The NIH also warns that “extremely high intakes of selenium can cause severe problems, including difficulty breathing, tremors, kidney failure, heart attacks, and heart failure.”

In 2015, 10 doctors from around the country appealed to Columbia University to take a stand against Oz by removing him from its medical school faculty.

“He has manifested an egregious lack of integrity by promoting quack treatments and cures in the interest of personal financial gain,” they wrote to Lee Goldman, dean of the faculties of health sciences and medicine.

The Oz show responded in a statement at the time that Oz delivers “the public information that will help them on their path to be their best selves.

“We provide multiple points of view, including mine, which is offered without conflict of interest.”

The university declined to take action, citing academic freedom. Oz became a professor emeritus in 2018 and retains that title, as well as special lecturer, according to a spokesperson for Columbia University’s Irving Medical Center.

A year before that letter, in 2014, Oz appeared before the Senate Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety and Insurance for a hearing on false advertising in the diet and weight-loss industry. Then-Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.), who chaired that panel, said she was driving and heard an advertisement plugging green coffee beans for weight loss. McCaskill, who said she has struggled with her weight her entire adult life, described feeling enraged and asked Oz, who had promoted these supplements, to testify.

“Imagine my shock when he said yes.” McCaskill said in an interview. “Which shows you the ego, the arrogance. He believed he was going to come in there and blow us all away with his charm and charisma. Okay, you want to do this? Let’s dance.”

Senators on the committee grilled Oz on the language he used on his show. Asked by then-Sen. Dean Heller (R-Nev.) whether he believed there was a magical cure for weight loss, Oz admitted that he did not know of one without diet and exercise.

“My job, I feel, on the show, is to be a cheerleader for the audience when they don’t think they have hope and they don’t think they can make it happen,” Oz told the senators. “It jump-starts you. It gives you the confidence to keep going.”

Alice Crites contributed to this report.

November’s midterm elections are likely to shift the political landscape and impact what President Biden can accomplish during the remainder of his first term. Here’s what to know.

When are the midterm elections? The general election is Nov. 8. Voters in more than half of the states will need to register before Election Day to cast a ballot. You can check your voter registration deadline here. If you’re voting by mail, here’s how to track your ballot.

Why are the midterms important? The midterm elections determine control of Congress: The party that has the House or Senate majority gets to organize the chamber and decide what legislation Congress considers. Thirty six governors and thousands of state legislators are also on the ballot. Here’s a complete guide to the midterms.

Which seats are up for election? Every seat in the House and a third of the seats in the 100-member Senate are up for election. Dozens of House members have already announced they will be retiring from Congress instead of seeking reelection.

Are you ready to vote? Answer a few questions and we will curate a personalized list of stories, explainers and graphics to prepare you to vote in the midterm elections on Nov. 8. Build your tool kit here.