- March 8, 2022

- No Comment

- 21 minutes read

The world's most expensive animals – BBC.com

Menu

One day, a duck called Big Dave was up for auction. An award-winning Muscovy drake that frequented the breeder shows, he was a fine specimen. “He’s got a very nice temperament. He’s always clean, he’s always looked after himself and when you show him he does like to be centre of attention,” his owner Graham Hicks told the BBC at the time.

Others couldn’t help but agree. Big Dave is a “big character”, said Janice Houghton-Wallace, a fellow breeder and secretary of the Turkey Club UK, and has always seemed to “have a great rapport with Graham.”

But Hicks was due to retire from breeding, so was reluctantly selling Dave, along with his other ducks, geese and birds. There were rumours that breeders from overseas were looking to acquire the drake for the potential of his bloodline.

As the auction began, though, there was surprise. Unknown to Hicks, Houghton-Wallace had assembled a syndicate, who had clubbed together to buy Dave. She entered the bidding at £900 ($1,250/€1,050), but the price continued to rise. After she placed the final bid, “the room went quiet and it seemed like forever before the hammer went down,” she recalled. She had won, with a bid of £1,500 ($2,070/€1,760) – a record-breaking sum for a duck.

The syndicate promptly gave Dave back to Hicks – the plan all along was to reunite the pair as a retirement gift. “We both sobbed on each others’ shoulders afterwards,” Houghton-Wallace recalled.

That day, Dave became the world’s most expensive duck, joining a select club of Earth’s most valuable animals. But while he could lay claim to be the diamond of ducks, there are many other species that are worth a great deal more.

So, what are the world’s most expensive animals? How do you even define the term? The answers are more complex than first appears.

Not Big Dave, but a similar Muscovy duck with a considerably lower price tag (Credit: Alamy)

Before we explore these questions, it’s worth acknowledging that ranking living creatures by their cost might feel a little fatuous to some, and even distasteful. Should animals be given economic value at all? Is it OK to put a price on a living, breathing creature? As we’ll discover later, there are certainly some who object to assigning economic prices to nature and wild creatures.

Yet the reality is, animals have always been a part of human economies, and the way people value some more than others can reveal striking truths about the world that we live in. Particularly so if you look at the prices people have been willing to pay for them.

You may also like:

Some of the most mind-boggling numbers can be found in the world of agriculture, where trading animals is commonplace. Consider one of the most ubiquitous farm creatures: the sheep. By some estimates, there are may be one billion sheep in the world, and most of them are not worth very much.

But somewhere in the UK, there’s a unique lamb called Double Diamond, who is worth an extraordinary amount of money. He doesn’t have a golden fleece; it’s his genetics that hold the value. He is a particularly impressive example of a Texel lamb, a breed that originates from a small island off the coast of the Netherlands.

In late 2020, a consortium of farmers bought him for 350,000 guineas – the traditional currency of livestock auctions. When converted, that’s £367,500 ($490,500/€411,300). “Don’t get me wrong, it is an obscene amount of money to pay for a sheep,” one of the consortium of farmers who bought him told BBC News. “We had to pay that amount of money to get the genetics.”

Double Diamond, a Texel lamb that sold for an "obscene amount of money for a sheep", poses with one of his prior owners (Credit: Catherine MacGregor/MacGregor Photography)

The world’s most expensive farm animal? Well, it beats the most expensive sheepdog, Kim the border collie, who was bought for £28,455 ($38,900/€33,300) in Wales in early 2021.

But there are cows and bulls that go for more. One of the most famous to sell for an eye-watering sum is Missy, a female Holstein who was bought for $1.2m (£865,000/€1m) in 2009. But even she has been eclipsed by her male counterparts. In 2019, an Angus bull called SAV America 8018 was sold to a former advisor to the Trump administration for $1.51m (£1.1m/€1.27m). The reason for such a steep price? The high value of this bull’s semen, which can be sold on.

An agricultural journalist at the auction described the privilege of meeting SAV America 8018 in person: “As soon as I went to open the gate, he came walking toward me, and sniffed my hand. He was as tame as a dog. His sheer power, width, and body were incredible. He stood on a big foot, with great substance of bone… a bull that will go down in history as one of the greats.”

Pet prices

But the farming industry is not the only domain of human life you will find staggeringly high prices paid for animals. Some people will pay a great deal of money for their pets.

Even the “average” pet can now command higher prices than a few years ago. In the UK, the price of dogs has shot up during the pandemic, with some breeds of puppy now selling for £3,000 ($4,160/€3,500). If you were to include the lifetime cost of feeding a dog, plus veterinary bills and other costs, pet-owners are paying tens of thousands.

The dog Big Splash sold for a record-breaking sum to a Chinese buyer (Credit: EPA)

But the record for the highest sum ever paid for a dog is far steeper: 10 million Chinese yuan, for a Tibetan mastiff called Big Splash. That’s £1.1m at today’s exchange rates ($1.55m/€1.3m). The mastiff breed has become something of a status symbol in China in recent years. But the high price, paid by a businessman who made his money in coal, could also have been an investment, since the dog has the potential to be hired out to other breeders.

What about cats? Among the priciest domestic breeds is the Savannah cat, which can cost almost $20,000 for a kitten (£14,400/€16,900). Guinness doesn’t hold a record for the most money paid for a cat, and as far as BBC Future is aware, no domestic feline comes close to the million-plus sum paid for Big Splash – but there are some cats that could rival him if you used other measurements of value.

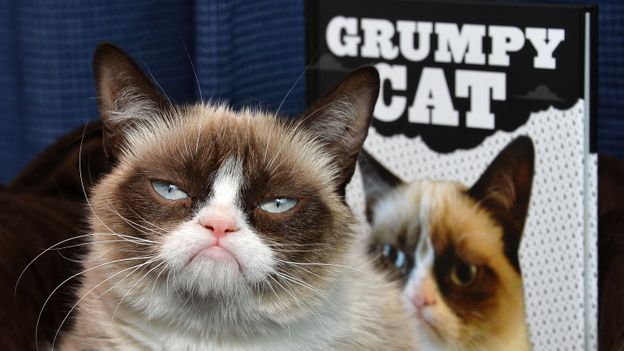

Grumpy Cat was – supposedly – worth tens of millions and was obviously delighted (Credit: Getty Images)

According to Guinness, the wealthiest ever cat was Blackie, who in 1988 was bequeathed a £7m fortune ($9.7m/€8.2m) after his owner, an antiques dealer, died and decided to snub his family. That said, there was a dog, Toby, who once inherited more – a whopping $15m (£10.8m/€12.6) in 1931 from his owner Ella Wendel, who was the last surviving member of a wealthy New York real estate family.

But if you look at wealth in terms of earnings, the internet star Grumpy Cat – real name Tardar Sauce – may be the frontrunner in the most expensive pet category. By some (admittedly hand-waving) estimates, she was worth around $100m (£71m/€84.5m) before she died. Or there’s musician Taylor Swift’s cat Olivia Benson, which has been given a similar valuation.

Racing value

However, the most money that’s ever been shelled out for an animal, at least according to Guinness World Records, has been for those that can race.

By weight, the most expensive animal in this category would be a bird. The most expensive pigeon is New Kim, which was sold to an anonymous bidder in China known only by the pseudonym “Super Duper”, for €1.6m ($1.8m/£1.4m) in late 2020.

While it may look like a typical street pigeon to the untrained eye, New Kim is worth €1.6m ($1.8m/£1.4m) (Credit: Alamy)

But perhaps unsurprisingly it is racehorses that command the highest prices. Guinness names the horse Seattle Dancer as the priciest, bought as a 1-2 year-old in 1985 for $13.1m (£9.4m/€11m). Sadly, Seattle Dancer would not have a stellar career: he caught a virus, and only competed five times.

Since then, other horses have sold for more: Fusaichi Pegasus, for example, was bought as a colt for $64m (£46m/€54m) in 2000. He fared better: winning six out of nine races, earning millions for his owners, but didn’t live up to his potential in terms of the quality of his offspring – again demonstrating that horse-racing is a gamble in more than one way. As of late 2020, he had been relieved of his duties and was “pensioned.”

Fusaichi Pegasus wins the Kentucky Derby race (Credit: Getty Images)

What about wild animals though? Is it possible to work out how much they are “worth”? There is a way, but it’s fundamentally different measure of value than market rate, and the two shouldn’t really be compared.

Over the past decade or two, scientists have attempted to put an economic value onto ecosystems by calculating the “services” they provide to human beings, from the food or resources they provide to more indirect benefits, such as carbon sequestration, pollination, or recreation and tourism.

The total value of the biosphere’s ecosystem services is therefore estimated to be up to $145 trillion a year (£104tn/€122tn). At a local scale, the calculations are generally done for a whole ecosystem – coastal wetlands, tropical forests and so on. So, the median value of coral reefs, for example, has been calculated at around $200,000 per hectare per year (£144,000/€168,000). Or it’s done by the service provided. For example, the global value of insect pollination services for crops has been estimated at around $180-500bn a year (£129-360bn/€150-420bn).

It’s far from precise as a technique – in fact, it’s a whole range of techniques, applied differently and inconsistently, according to the researchers Annelies Boerema and Alanna Rebelo and colleagues, who reviewed more than 400 papers on the topic in 2016.

The tourism value of sharks is worth millions to economies (Credit: Brad Leue/Getty Images)

There are some who object to valuing nature by specific services, arguing it fails to capture unquantifiable traits of the natural world, such as the psychological wellbeing that it provides. Others say that ecocsystems and living things should be seen as priceless.

But the thinking is that it can motivate people to see natural ecosystems in whole new ways – especially people who only ever think economically. “The whole aim of this concept is to get people to think holistically,” says Rebelo. “In that sense, the concept will always be useful, no matter how flawed it is. The aim is for better stewardship, not only for current generations but future generations.”

So, what can this approach tell us about the value of specific animals? While the majority of calculations take a birds-eye view of ecosystems or services as a whole, a few studies have calculated the value of specific taxonomic species, genera or orders.

In 2015, BBC Earth compiled a whole series of these valuations for an interactive game (the site is no longer available online, but the list is archived here). So for example, the total value of sharks for tourism is around $944m (£682m/€799m), the cowpat-tidying services of dung beetles has been estimated at $380m (£274m/€321m), and in Canada alone, polar bears can be valued at $6.3bn (£4.5bn/$5.3bn).

You could, in principle, do some crude sums to calculate the value of each of these individual animals, by dividing by population. That would give a value for each one of the roughly 16,000 Canadian polar bears as around $400,000 per bear (£289,000/€338,000).

But recently, Ralph Chami at the International Monetary Fund and his colleagues applied this kind of “single animal” approach more rigorously. Their goal? To calculate the value for individual African forest elephants, and great whales off the coast of South America.

African forest elephants make a million-dollar contribution to carbon capture (Credit: Getty Images)

Megafauna such as these provide various services, from ecotourism revenue to acting as beasts of burden. But less obviously, both elephants and whales also help to sequester carbon, within in their bodies and through their feeding habits. (As do many other animals, such as sea otters, which BBC Future Planet reported on earlier this week.)

Looking specifically at the animals’ carbon capture potential, now and in the future, Chami and colleagues calculated a value of $1.8m (£1.27m/€1.5m) per elephant. The whales had a similarly high price. The numbers varied from $165,000 (£120,000/€140,000) for a Minke whale up to $4m (£2.9m/€3.4m) for a blue whale, but most of the whales came out with having a value of about $2m (£1.45/€1.7m).

Chami and colleagues argue that it helps to have a value for individual animals, because of its psychological power to incline people towards conservation. After all, charities like WWF tend to use imagery and stories of charismatic megafauna to encourage donations. If a financial figure for an individual elephant was used in a conservation campaign, it could help to “educate the public about elephants’ contributions to carbon capture, and convince individuals to spend their resources on preservation of this species and its habitat,” they write.

A dollar sum for an elephant or whale could also be used to define fines and penalties for those that would harm them, such as poachers, ships or illegal whaling vessels. The elephant’s valuation was notably far more than what they are worth on the black market: a tusk fetches around $20,000 (£14,500/€17,000). And a ship that strikes and kills a blue whale off the coast of Brazil should be fined the full value of the whale, say Chami and colleagues.

It should be obvious, however, that this does not tell us that elephants and whales are the most “valuable” animals in nature. Unless a full accounting of the natural world were done, we won’t know. And even if it was, it might be difficult to compare figures, because the techniques deployed would all vary so much, not all services would be captured, and relationships between animals within ecosystems are difficult to unpick. (For these reasons, among others, Boerema and Rebelo point out that many existing ecosystem service values are probably too conservative.)

If a boat harms a blue whale, should the penalty be commensurate to its ecosystem service value? (Credit: Getty Images/Mark Carwardine)

So where does that leave us in the search for the most “expensive” animal? It’s clear that there are no easy answers. If you try to work it out by the simplest measure of market price paid, it’s fairly clear the racehorse that would sit at the top of the list – but as we’ve explored, there are other economically valuable or wealthy animals that are not available to “buy”.

However, there is one animal that we haven’t mentioned yet, that might well have a strong case to top the list of most financially valuable animals: the giant panda. It’s certainly the most expensive zoo species, according to Guinness, but it’s true value may be higher still.

Why so? The entire population is owned by China, and many zoos – particularly in the US – must pay a leasing fee to host them, of up to $1m per year (£723,000/$845,000). Given that many captive pandas have lived into their 20s, that adds up to a hefty sum. If cubs are born, a one-off payment of up to $600,000 (£434,000/€507,000) must reportedly be paid too. Factor in the rarity, cultural value, conservation investment – and the “panda diplomacy” that couples their leases to trade talks worth hundreds of millions – then their true value could be far, far higher.

Could the giant panda be the world's most valuable animal? To China it is (Credit: Tim Sloan/Getty Images)

So, in the list of most expensive animals, there are some very valuable individuals indeed – pandas, elephants, whales, dogs, cats and horses that would collectively add up to billions in value.

And then there’s Big Dave the duck. Certainly not the priciest animal, but still deserving of his place in the club. For his owner Graham Hicks, though, the drake’s price tag probably wasn’t so relevant. As the delighted breeder put it when discovering that he and Dave would be spending retirement together: “He’s been a very good friend.”

*Richard Fisher is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets @rifish

—

Note: All currency conversions are based on today’s rates, and prices have not been adjusted for inflation.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.