- September 3, 2022

- No Comment

- 35 minutes read

In Conversation with Gary Farmer of Reservation Dogs – Mpls.St.Paul Magazine

The Native actor and musician will make an appearance at the the upcoming Water is Life festival in Duluth’s Bayfront Park.

by Steve Marsh

September 2, 2022

3:05 PM

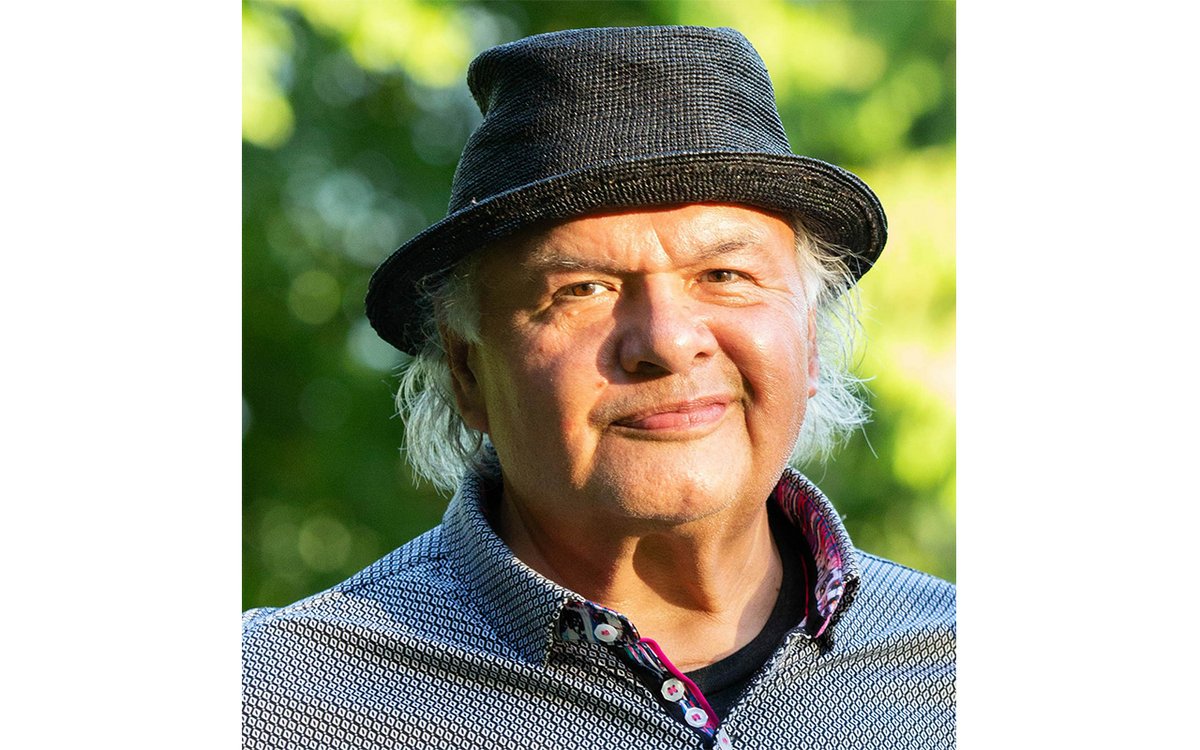

Gary Farmer

One of the reasons the upcoming Water is Life concert is so special—the benefit concert for Winona LaDuke’s Honor the Earth going down again in Duluth’s Bayfront Park on Sunday—is because it’s a showcase for the importance of Native life and art to all of our lives. And when they announced the actor and musician Gary Farmer was going to make an appearance, it underlined that aspect of the festival. Because Farmer means so much to so many people, especially Native people.

Farmer is a deep artist whose work has modeled so many aspects of Native life. In the nineties, he kind of grew up before our eyes in a holy trinity of roles: first playing Philbert, the young Native warrior trying to find his place in the modern world in 1989’s seminal Powwow Highway; then, probably most famously playing Nobody, the trickster Virgil to Johnny Depp’s fading Dante in Jim Jarmusch’s po-mo Western Dead Man in 1995; and in 1998 the beautifully complex, on-the-verge-of absentee dad Arnold in Smoke Signals. He’s been in dozens of movies since, some roles sincere, some hilarious, some dark. Right now, he’s having a streaming TV moment as Uncle Brownie in Sterlin Harjo’s acclaimed Reservation Dogs. Farmer is always human, always real. And that goes for off camera too: When I got him on the phone from his home in Santa Fe he says he’s not doing bad, “for an old guy.” When I try to be helpful explaining that 69 isn’t that bad, he says, “Well, Indian and 69 don’t go together—I should’ve died ten years ago according to the statistics.”

You’re going to be singing and playing harmonica with your longtime friend Keith Secola at the Water is Life concert. It’s impossible not to think about Keith’s great song, “NDN Kars,” and the fact that you drove one of the most classic “Indian cars” of all times in Powwow Highway.

He tried to sell it to the film! [The director] Jonathan Wacks didn’t go for it. Of course he had Robbie Robertson and Credence Clearwater Revival songs. In retrospect, I’m sure he would’ve, but it’s not that Keith didn’t try. We did get “NDN Kars” into a series I’m also doing besides Reservation Dogs, called Resident Alien, under NBC Universal. It’s on the Syfy Network. We got his song in that show last season.

Oh that’s great. I haven’t seen Resident Alien yet, but I’m loving Reservation Dogs. The whole show is centered around grief, and you’re not like an official medicine man but you recently got a direct connection to the spirt world through the Dakota spirit played by Dallas Goldtooth. And then I was thinking, Dead Man was about grief. And like you said in the beginning of our conversation, you feel lucky to be alive, a Native American at 69.

For real. I mean, ancestors—the people around you, your community, whether they’re here or not, they’re always with you. And that’s never changed for me, I grew up that way. There’s always loss in life, and we always have to acknowledge it in order to move forward.

This concert is benefitting Winona LaDuke’s environmental group Honor the Earth, and she’s been fighting pipelines her whole life. But her fight against Line 3 failed when the replacement was finished last year. Sometimes environmental activism can feel like the premise of Dead Man, where your character Nobody knows that Johnny Depp’s character William Blake is already a goner, a walking dead man. How do we find hope?

That’s the struggle. That’s why we have the concert, we have to continue, as artists, to try and enlighten the larger society because they’ve lost sight of the reality of it, they live in a different world. It’s really hard to explain to a journalist that we still got to continue to work at the bottom politic to help them see the longer vision in a very short term focused society. I mean, look at their elections. Who can lead for four years realistically in this work? That’s absurd. Our leadership was chosen for life, so then you can envision seven generations from the four-year election term.

So you live in Santa Fe now?

Yeah, I have for a long time.

But you’re from the Cayuga community in Canada?

Well, it’s called the Six Nations along the Grand River. It’s where all the Haudenosaunee or the Iroquois Confederacy are. The fire was split during the American Revolution, War of 1812. So half of us sided with Washington, and half of us sided with the British and fought against the Americans. It’s the only reason Canada exists—we were the Vietcong of the day. We were forest fighters, the British were still marching up and down like that. And as far as I’m concerned, the Haudenosaunee or the Six Nations are the reason that Canada is even there.

Wow. And it’s your tradition up there to elect tribal leadership or Six Nation leadership for lifetime appointments?

That confederacy still exists, it represents a lot of our lands and entitlements. But the day-to-day administration is a band council—band councils they call them, and they’re elected every two years. The traditional still exists, but they’ve been in conflict because we lived off a maternalistic system, so grandmothers would choose those leaders for life. But as life got more challenging with health and such, the grandmothers began to choose their own sons. So the leadership wasn’t as valiant as it was in the past generations. And of course, Franklin and all those guys drew up their constitution based on concepts of our government because we’re known as the people of government in the Indigenous world, and they took that.

For instance, grandmothers would select leadership, but if you look at who selects leadership in this country, it’s the electoral college, it’s very corrupt. It’s not the women. I’d be interested to see if the electoral college was made up of only women, I think we’d be better off. So the concept of getting rid of the paternalistic system—it’s not that old, it’s 150 years old. And it’s not working obviously, so it’s time to go back to the maternal way. Let the women choose leadership. And it’s happening in a way, it’s happening and it’s coming back. We know we can’t exist forever under the paternalistic system. Just take a look at Donald Trump.

So when did you first meet Winona? I know she had a cameo on that movie, Skins, which was the director of Smoke Signals’s follow-up movie. Did you meet her then or did you meet her a long time ago?

Yeah, I knew Winona’s dad briefly. Her first marriage was to my best friend in college, from James Bay, Ontario. She married him and had two children. Winona would come to visit during my tenure up at Eddie’s lodge up in Northern Wisconsin on Lake Superior, so I’ve know her for a long time. But we’re not close—I’m looking forward to working with her on this concert, but we haven’t spent a lot of time together primarily because I’m northeast or southwest.

And she’s Midwest.

But I know Minneapolis and Minnesota. I’ve toured through all those communities in Minnesota over the years. And I’ve spent a lot of time at the colleges in Duluth and Minneapolis and the Indian centers. It’s a small community really in North America when you look at it.

Oh, for sure. I mean, like, you just told me that Winona was married to your best friend in college.

Well, she was married to the brother of my best friend.

Yeah, the Native community is such a small world, right?

He actually passed several years ago. The day after he came to my show in downtown Minneapolis. I was touring at the time, and that was a very traumatic day. After spending time with him the night before, he had an evening heart attack, took his life in the morning by wake-up time. So that was her husband that more bore the two children, but she’s taken on a lot more children. And I’ve always respected Winona for all the work she does, and I’m happy to be present and be there with her at this time.

The Native writer and historian David Treuer recently wrote in The Atlantic about how Reservation Dogs has a feel that it’s been written and produced for a Native audience first. I mean, clearly millions of white people watch it as well. But the fact that there’s two audiences for something—it’s a problem that messed Dave Chappelle up in his career. I mean, I think in the movie Dead Man, your character of Nobody, this was maybe Jarmusch’s poetic take on this idea of what an audience is for, who art is for, and are white people laughing with you or at you. Nobody was rejected by both his Native family and white society. You’ve been on both sides—you’ve done so many independent, smaller, but cherished Native movies, and then you’ve done big movies with Robert De Niro and stuff. So is this something that you think about?

The only reason that Dead Man didn’t get distribution in North America—Christ, we had Robert Mitchum in the film—was because of Harvey Weinstein. The distributor for the film in America killed it for his own reasons.

What were his reasons, do you know?

I’m sure you can reach him in prison. I’m sure he’d love to talk about it now—asshole. But the film industry is, like most industries in America, corrupt. I mean, when you got someone like CNN, still not recognizing Native America or the other—or whatever they call us, “something else” I guess was the term. America lives on a lie—and has had to live in a lie in order to make sure people continue to pay their fucking taxes, continue to pay all these people to continue to rip it off for all of its resources and lining the pockets of the political elite. It’s a very sad system to watch, it’s very disturbing. I think America is Indian when you’re talking about it. I mean, there was a hundred million of us here in North Central America and they either married us and fucked us, or they killed us. So a lot of blood in these American people, but there’s this war of attrition going on with whites feeling that the people of color are going to overtake the continent with population, and so we’re having to suffer through this last bastion of white control, paternalistic thinking. And eventually, it’ll die off—it’ll have to, or the Earth will react like it did with COVID, to set everybody down to think again. And we’ve been at this point before. If you look at the Mayan calendar, we’ve been here before and humans weren’t able to make the right choice before. So let’s see if it happens this time with a little bit more knowledge. The media has opened up for us a little bit more, we need more control of our own networks so that we can start to protect Central and South America because that’s where the major attacks are going now.

Absolutely.

There’s a reason why they like to split us. There’s a reason why they plant bombs through an Indian market in Santa Fe at the creative high school. Why are they planting bombs through an Indian market? They’ll do anything to help Americans understand their place in the world in this world today. They’ll do anything to exploit and play down the real history of this country because it’ll crack it up, which it probably should be broken up now.

You know why I live in New Mexico? Because the tribal people take care of this place with ceremony. That trail of tears, when they chased all those Indian people away back in 1800s, they did it for the land, but they forgot that these people are the caretakers of the land. They do ceremonies specifically to maintain the land and protect this from tornadoes and hurricanes and floods. You look at the South how much they suffer, it’s because they chase their Indians out. We take care of this place and Americans don’t understand that, and I don’t want to call them ignorant, but they are, and I’m sick of it. In my 69th year, it’s really hard to talk to you about this because I’m so sick and tired of it.

No, I get you. You’re saying implicit to my question about audiences is a rhetorical separation. Maybe I shouldn’t be thinking of myself as, like, I’m a white guy and you’re a Native guy. Maybe I should be just thinking of like, hey, we’re all in this together.

Are you a human being who exploits or a human being who understands their place in the world and how we all fit in together?

No doubt.

If you don’t understand that, you’re a lost child.

I do understand that, and I feel very lucky to have grown up in Minnesota where the Dakota and the Ojibwe are still here, where they never left, where they remain as powerful parts of our society. And we have people like Winona LaDuke putting on concerts and getting people together to think about being human beings that need the Earth to be healthy in order to go forward. So, yeah, man, I’m very appreciative of my place in it all.

And all the major networks play along. They all play along, they have to, that’s their job, right? So television’s still in control in a way, that’s why we need to break away. I mean, I tried to do it over radio, because radio’s the most honest medium we have. Television puts your mind into beta so you become a receiver of information. Radio, at the sound of my voice, you’re creating images in your own mind, it’s a far more creative medium. And that’s how we lived as an oral culture, that’s how we took everything forward was orally, nothing’s written down. And when the people tried to suppress my people back in the 1600, 1700s, they took our Wampum belts thinking that we couldn’t exist any longer, trying to take our government away from us so that we would be subservient to them and be the worker bees for them, and some people did. But we gained our culture, integrity, language, everything. My language in my community’s stronger than it’s been in a century.

So in a lot of your movies, you speak several different Native languages. Which ones are you fluent in?

I’m only fluent—somewhat fluent, not even, in my own community language. And all of our ceremonial life is conducted in our language, so when I get home to the ceremonies, that’s when I hear my language. I do hear it in daily conversation at home. Remember, I was born in ’53. Basically, I was Nobody. I was taken from the reserve, raised in Buffalo, New York with Italian, Polish, and Irish immigrants, and I felt like Nobody, that’s what I directly related it to. And then at the end, me and Jim argued for a while about Dead Man. I never thought I was the Dead Man. I said, hey, according to the story they run by, the meek should inherit the Earth. I’m not dead, Nobody doesn’t die. That’s why he put Nobody in Ghost Dog with Forrest Whitaker, just for a scene. It tied the circle up that, yeah, it’s just not the same world.

So is Nobody actually alive until the end of the movie? He’s not like some figment of William Blake’s imagination or vice versa, right? It’s such a dreamy, strange movie. Did you play him as if he really exists in real life in the film? Like you’re not like a dream character or something?

No, no, in order to have the vision of how to get him ready to prepare for this next move into the spirit world, we had a ceremony, right? We used peyote. It wasn’t always conducted in the proper order, but basically I helped him envision getting back to the next world. He was a spirit. And he was a spirit that moved me—one of the few. And of course, William Blake was chastised for believing that a tree was the same as a human—which is true. But he was trashed by the people in his time—everyone thought he was crazy.

So humans are very arrogant, right? Where they think that they’re more than the life of a tree or any animal on the planet. Up where Winona’s husband used to live, they flooded a million acres of land. I don’t know if you know about the James Bay Project. It’s all the electricity for New York. It’s basically a million acres in the center of Quebec that they flooded to create a hydroelectric plant to supply energy to the Northeast. Now, my argument is, you got to be Christian to do that. You can’t be anything else to do that kind of environmental degradation because they can be forgiven the next day as far as their church goes, right? You can take out a million acres of land and animals and life and relocate the human beings to wherever you want for the technology to progress and create economy for everybody who’s tied into that economy, but they don’t have any conscience really. They can do that, but you got to be Christian to do that. And that’s the scary part, right? That’s the scary part, where you’ve taken religion to the point where you can destroy Earth under God’s name, whatever that is to you. And so we’re talking deep now, but I know you can’t write about that.

We can go as deep as you want. I think historically, one of the biggest causes of ecological disaster, as big or bigger than oil and fossil fuels, is just dams. Dams are horribly destructive.

Really. And we can run off the sun. The sun can supply everything we need. There’s too much money being made otherwise to flood a million acres of land.

Growing up in Buffalo, your dad was an engineer, wasn’t he?

He built a hydroelectric dam at the falls there.

So how long did it take for you to unlearn some of the ideas that you had grown up with?

Well, I’ve worked with story my whole life, since I was 18 years old. I’ve been a performer of one kind or another and I tell people’s stories. I’m close to my tribe, I go to ceremonial life, not only in my own tribe, but all tribes. When I did Powwow Highway—I’m an Eastern Great Lakes Indian, I knew nothing of northern culture and history [editor’s note: he plays a Cheyenne in the movie]. I educated myself through my work—that’s why I do it. It broadens my perspective on the bigger issues, it really has. It’s been a good life that way, to come back around to who we are as Indigenous people. And we have to operate in this English language—that’s okay. I’ve learned to explain myself in their language to be able to help reach a larger audience, to turn things around. That’s my role: to make things better for everybody. Not just my own, everybody.

I thought about your role in the culture while watching some of your films this last weekend. Seeing the activist John Trudell in both Powwow Highway and Smoke Signals. And I thought about the great AIM activist Russell Means who was also an actor. And your scene partner in Dead Man, Michelle Thrush, who is also a Native activist.

Sitting Bull became an actor. With Buffalo Bill.

That’s right.

Pauline Johnson, a girl from my own community, was touring poetry as a woman on the back of a train when Wounded Knee happened in 1875. That blows me away.

So is it maybe just by default Native artists are activists?

Well, we’ve had to be. When I was first on that set of Powwow Highway, John took the time to educate me his story. We sat for hours when we first met, as he told me everything from his perspective. Dennis Banks was a dear friend. I toured around with him. I would find him in communities and put him in films because he just happened to be there. Russell lived in Santa Fe here with me for years. All those guys, I know their stories, I know there’s a lot of dark to their stories, too, and had to uncover that slowly. The tragedy of Anna Mae Aquash when after John burnt the flag on the American steps, the FBI, the CIA, they all invaded AIM, and it became like a Shakespeare play. it’s tragic, but that was the truth. Everyone thought everybody was a spy, and the real spy is still out there, still operating, actually. Some of us know who he is. It’s a tricky world—we all know each other in the artistic community, who’s there for each other. We know.

It has been a joy to watch you working with Wes Studi on Reservations Dogs, back together decades after breaking in together on Powwow Highway. I saw a film critic say Powwow Highway is like the Native American Outsiders. And now you’re the elders on Reservation Dogs. So what’s some of the wisdom you share with your young castmates?

Well, the young are coming up, but I think we’re bringing them in the good way. Those four in Reservation Dogs going to have a long career if they so choose. I was talking to one of them on the last shoot and he says, “I only do this because my mom wants me to.”

Ha. Which one of them said that?

The third one, the youngest one, 15.

Lane Factor, who plays Cheese.

Probably the best actor out of all of them, actually. So normal, he’s just a great guy. He just is who he is and it’s just wonderful. I mean, he’s going to have a wonderful career as an actor in the business, and being with us all these years. Because I expect this series is going to run. We’re going to do a third season soon I’m sure, and the longer we spend with them, they’re going to just pick up everything. And then all those kids on the reservations learning that language, they’re going to make America stronger than ever. We’ve prepared the young for this movement. It’s going to be overwhelming for Americans once we deal with these Southern white issues of racists who can’t get over themselves kind of stuff.

What is some of the wisdom that you guys share? Is there anything you would’ve done differently if you had a second chance?

Well, for instance, Bear, D’Pharaoh Woon-A-tai—I grew up with his grandpa. His grandfather started the first Indian school in a language school in Toronto when I was a student at University and I drove a cab and bounced at the local Indian bar. I started in photography and motion picture production, and his grandpa is the one that got the Indian Health Center together, also in downtown Toronto. So I’ve known his family for generations. That young girl [Paulina Alexis, who plays Willie Jack] come from Saskatchewan, the Crees. I’ve been out there with them Crees in Saskatchewan for years, at Powwows, at different events, shooting films. I know their community. All I got to know is she’s from near Edmonton, and we know all those people. That other girl, Devery Jacobs, she’s from Kahnawake, I’m from Oshweken, we’re the same Haudenosaunee people—she’s Mohawk, I’m Cayuga, that’s part of the Six Nations, we speak the same language. I can speak Mohawk a little bit.

I had to do a Columbus Day speech for Cincinnati, Ohio, I do a little bit of research. That is 300 miles from my home community, maybe down along that Mississippi Valley. You know there’s Cayugas and Senecas down in Northeast Oklahoma. Prior to contact of the Whites, the Haudenosaunee literally controlled the Saint Lawrence River, all up and down it, all through Ontario, Quebec, all of New York. The Delaware were going to join the confederacy if it wasn’t for the American Revolution. The Tutelos were going to join the confederation, Wyandots were going to join—we would’ve been nine nations had it not been for the American movement. Anyway, I did the research, and I found an anthropologist and an archeologist—he’s got degrees in both, he speaks Seneca. The fellow writes me back in Seneca at the University of Cincinnati. There’s a community 20 miles northeast of Cincinnati, he says, 14,000 years old. He also did the research to find that the same people from that 14,000-year-old community in Cincinnati, when the Americans came there 300 years ago, it’s the same people from 14,000 years ago. That whole territory was my people’s territory, down the Mississippi, all the way down to Oklahoma, all the way up to St. Lawrence, that’s how much area we used to have and live and trade. And we used to follow the eagle to the flight of the condor, and that’s where all the trade come from. Two hundred varieties beans, that’s how sophisticated we were with farming. There’s so much to learn in America about who they really are. They’d be so proud if they knew.

And so that’s what you’re telling these kids: that you have 14,000 years worth of wisdom to learn.

Yeah. We’ve been here forever. That fucking Bering Strait thing—my current girlfriend’s father ran Los Alamos. He’s coming to ask me, Gary, please tell me about the Bering Strait. I learned this from a Maori elder that people went both ways on the Bering Strait. The Monterey came up from Easter Island and they say they’re the bravest, they came to the Mother, which is here in North America. And they went across that strait and they went down to the state of Mau and they lost some people. And they were the brave and the strongest because they sailed the farthest, they were very good at sailing and reading the stars. Those migrations went everywhere. This whole Bering Strait theory that we came from the same place so the Americans can take the entire continent. They just created this fiction so that they could justify themselves to all of this.

I really love your work, you seem like a real-ass dude and you bring that to each role. Like you said, you’re learning all the time and bringing so many different aspects of experience with you, and it’s generous of you to draw on your own kind of personal family joy and trauma and to bring that to certain roles. That’s brave shit and you’re living it. I imagined with your Uncle Brownie character, you’re drawing on your own family history as well.

I pitch ideas to them all the time for Brownie. It’s really fun. I’ve never been on a set before like that. I was in another show called Resident Alien, it’s as creative as Reservation Dogs in a certain way. But we have limitations as Native characters in that show, we’re not the leads. But we still have an impact through cultural integrity, the tribes where we’re representing, and in the case of Reservation Dogs, it’s youth, which I’m not. So I’m learning more about youth culture at the same time. And it’s a fascinating life to be able to bring stories to people and affect their lives long term.

The impact Powwow Highway‘s had on a generation and then their children are impacted by Smoke Signals and Dead Man, and then now, Reservation Dogs, is a whole new generation. So I’ve been through three generations of peoples, and I had people come, “Oh, my favorite film is Powwow Highway,” and they’re 60 plus. “Oh, my favorite film is Smoke Signals,” and they’re 40 plus. And, “Oh, I love Reservation Dogs.” it’s the 20-year-olds that are going crazy right now for Brownie and everybody in the show. I never had so many young fans as I do now, so, yeah, we’re reaching them. And this show’s going to carry on forever as far as I can see. As long as the creators want to continue to tell those stories.

I’ll tell you a quick story. You mentioned The Score, where I worked with Robert De Niro, Edward Norton, and Angela Bassett on Marlon Brando’s last movie. I remember the first day we read that script. I don’t know if you’ve seen the movie, but it worked out pretty good in the end. But we didn’t really have a script. After the first read, I remember this actor, Maury Chaykin, dear friend of mine, he came in to read Marlon’s part because Marlon wasn’t there yet. And after the read, we all looked at each other and said, “Fuck, this needs some work.”

I instantly go to Frank Oz—who’s Miss Piggy [editor’s note: Frank Oz was a former Muppet Show puppeteer who Marlon Brando would call Miss Piggy on set]. Marlon took offense to Frank because he was Miss Piggy, and he wouldn’t let Marlon be pink and gay for this role, so Marlon just punished them. Anyway, they needed story, and my character’s a smuggler, so I go to my own people, who knows about smuggling a little bit. Well, I said to Robert De Niro, come on, I’ll take you home, these people will open up to you, I checked on my way up, they’re ready to open up to you. But Robert couldn’t do that. Let’s go into Indian country, we’ll tell you a story, Robert! He couldn’t let it go.

Marlon Brando, though, he seemed to be extremely comfortable with Native communities, with his activism.

I can’t go into that, but I asked Marlon a really dumb question because he was in a place when Anna Mae Aquash got murdered, and he didn’t want to deal with that. He didn’t want to talk about it. But he was 80 then, I don’t blame him. Me, I’ll open up to say any fucking thing right now. I’ll tell you what happened. And a lot of people didn’t like that because you got to play along. I’ve never played along. I probably walked off as many sets as I stayed on, so fuck them, I don’t care. That’s not why I’m here. I’m here to make it better for every motherfucker, and I don’t care. So you want to fire my ass, send me home, I don’t care, I can survive. So I don’t play along like most people do. Robert had to do every fucking thing because the tax people got a hold of him, right? That’s why he did every fucking movie, because he had to.

Wow. So how are you going to boil down 14,000 years of wisdom into a 10-minute talk before Secola’s set on Sunday?

I get to listen to everybody else and I’ll fit in as it seems fitting, and I’ll see if I can take the narrative a little farther if they allow it.

Well, I suppose that’s how you work as an actor, right? You listen and then you react.

Exactly. You got to be aware of everything around you and all the people that are there. And you know the strengths they got because I know all these people. I’m looking forward to watching Ani DiFranco, she’s from Jamestown, New York, and I grew up in Buffalo—she claims Buffalo a bit. The Indigo Girls, I have a friend here in Santa Fe going to make a feature documentary on them—it’s almost finished. I don’t know those girls too well. I know Winona’s had wonderful relationships with these performers, and I’m looking forward to meeting some of my heroes. Any woman that can sing and sustain over the course of history here is vital to our success, I believe.

Steve Marsh is a senior writer at Mpls.St.Paul Magazine.

September 2, 2022

3:05 PM

Sign up for our daily newsletter.

The arts and entertainment blog. Read more

var customEventsOnLoad = window.onload;

window.onload = function()

{ customEventsOnLoad();

var myStringArray = mp_global.tag;

var arrayLength = myStringArray.length;

for (var i = 0; i < arrayLength; i++) {

ewt.track({name:mp_global.tag[i],type:'topiccode'});

}

}

©

document.write(new Date().getFullYear());

Key Enterprises LLC

All rights reserved

Key Enterprise LLC is committed to ensuring digital accessibility for mspmag.com for people with disabilities. We are continually improving the user experience for everyone, and applying the relevant accessibility standards.