- July 28, 2022

- No Comment

- 13 minutes read

Cancer care for pets is hugely costly – The Washington Post

When my happy, energetic 12-year-old mutt had what appeared to be an eye infection, I didn’t think much of it and took him to the veterinarian. A few X-rays later, that watery eye turned out to be the result of a tumor. I was distraught. Blue needed to see a specialist.

A few days later, a veterinary oncologist lifted my spirits when she said there was, indeed, something that could be done. But then, she started talking about money: It would cost thousands of dollars.

I had already spent about $2,000 in three days at the two vet practices. The CT scan Blue needed next would be another $2,500, and radiation therapy after that could cost at least $9,500 more.

This is a problem that many pet owners face: Medical bills for a dog or cat can easily run into the thousands of dollars. But for many of us, these are beloved family members. And some 86 percent have said we would pay whatever it takes if a pet needed extensive veterinary care.

That sentiment is more about love than actual math. It was a cold shock of reality when I added up Blue’s total projected expenses on paper. Getting the best available treatment for his tumor could cost more than $15,000 — and that was if everything went right. I’d already spent a lot. And it was unclear how much time it would buy him.

The oncologist at NorthStar VETS in New Jersey said they make sure pet owners understand up front what they’re getting into financially because many people can’t afford that kind of cost — many don’t have enough money in the bank to cover their own, or their kids, medical care. The call like the one I got is usually the heartbreaking beginning of the end of their pet’s story.

Like human health care, veterinary care is a marketplace of spiraling expense. According to the American Pet Products Association, pet owners in 2021 spent $34.3 billion on veterinary care and products, up from $24 billion in 2010.

And just as with human health care, there are now advanced treatments for pets in a range of vet fields, including dermatology, ophthalmology, orthopedics and, in my dog’s case, oncology.

The founder of NorthStar VETS added radiation oncology to his clinic’s services after his own dog had a brain tumor in 2014. He had to drive from New Jersey to Pennsylvania to find radiation therapy that cured the cancer, so he partnered with a company called PetCure Oncology to open a radiation center on NorthStar’s campus in May 2021.

And that was where my adopted shelter mutt ended up for treatment a year later.

PetCure provides something called stereotactic radiation. This is a gold-standard radiation treatment for humans: In 2015, former president Jimmy Carter had stereotactic radiation for melanoma in his brain; in 2019, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had it for a tumor on her pancreas.

For dogs, stereotactic radiation has been mostly available in veterinary teaching hospitals affiliated with universities and a handful of private practices nationwide. If pet owners live near one of those places and have the financial wherewithal, their beloved animals can receive the same cancer treatment as a former president and a justice.

“It is exactly what humans with cancer get in human oncology centers all the time,” says Ben Chiswick, vice president of operations and growth at PetCure. “It’s much more precise and impactful than other forms of radiation therapy. The more precise that beam of radiation can be going to the tumor, the less that beam is going to touch surrounding, healthy tissue, which is where the side effects come from.”

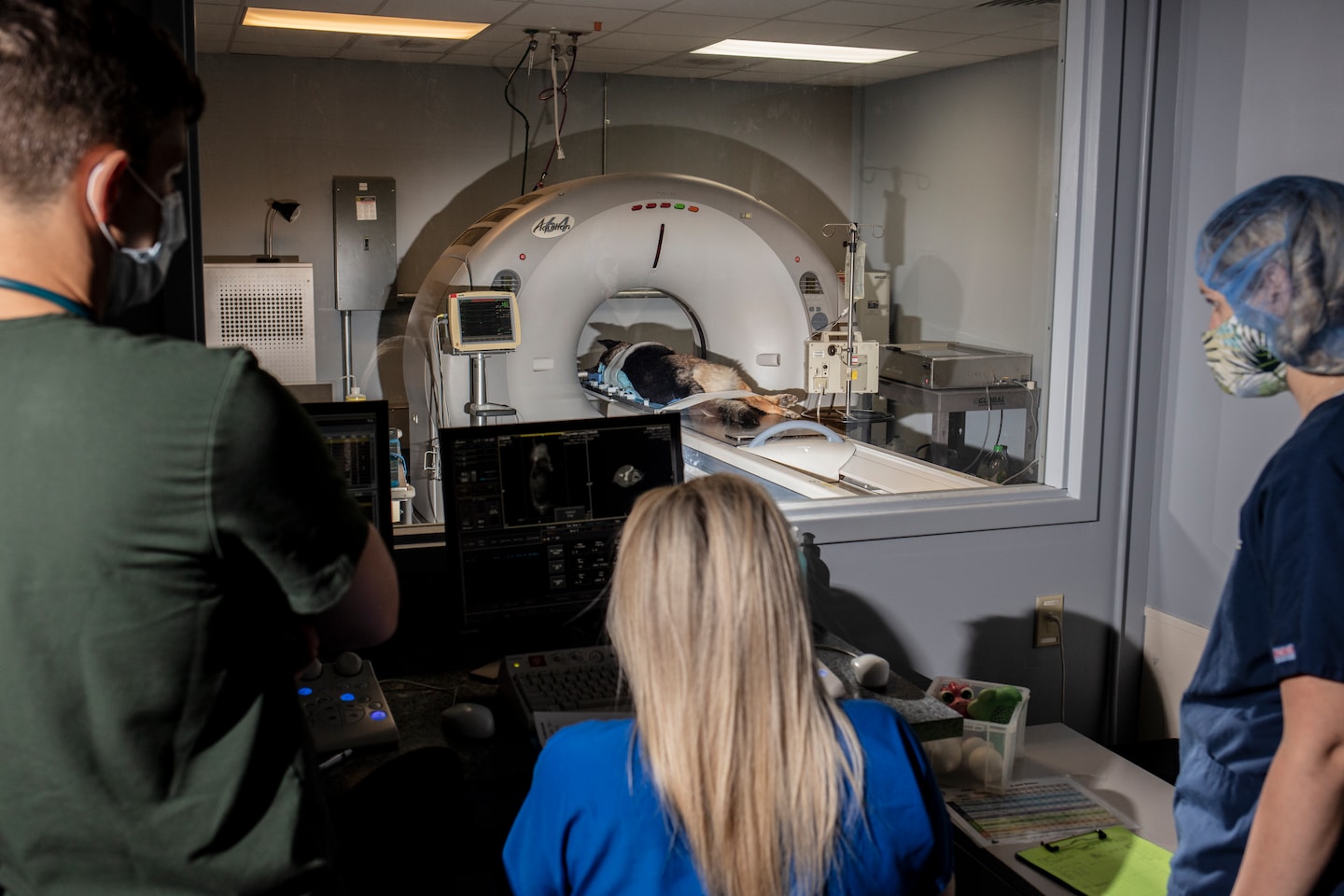

Stereotactic radiation is done over the course of one to three days, each time with the dog under anesthesia. In Blue’s case, the recommendation was for a three-day regimen with cumulative anesthesia and radiation effects that would leave him briefly disoriented and mostly exhausted, but still a lot better off than with traditional radiation courses that take place daily over several weeks.

I lucked out living near that clinic. After spending $5,000 on vet bills for a previous dog’s leg injury, I also had bought pet insurance when I adopted Blue II. Over the course of his life, the premiums averaged about $700 a year — less than many human health insurance policies cost for a single month. Maybe I’d never I’d use it, but if Blue needed it, it was there.

Now he needed it. When I asked the specialist on the phone whether Blue’s pet insurance policy would reimburse me for this type of radiation therapy, the answer was yes. So I greenlit the CT scan, checked the available credit on my Mastercard to cover the costs until insurance reimbursement arrived and rushed to get him into the radiation machine faster than his tumor was growing.

Over 100,000 veterinarians work in the United States, but a spike in pandemic pets and a huge demand for care have meant long wait times for many pet owners. Veterinary oncology is even less accessible. Only about 1,000 vets have degrees in medical or radiation oncology or surgery. Getting access to one can take four to six weeks nationwide, Chiswick says; every place I called near my home in New Jersey told me the wait would be two to six weeks just for an initial consult.

My regular vet said that wasn’t fast enough. Blue needed us to find a way to do better.

And so, I got up at 3 a.m., drove to NorthStar’s emergency department at a time when it was most likely to be empty and waited several hours while persuading them to admit Blue for a consult. My regular vet had sent his paperwork and X-rays over digitally.

The NorthStar emergency vet told me not to bother waiting; an oncologist might get to Blue that day, or maybe the next day. He would have to sit in the back until, well, whenever they could squeeze him in.Luckily, the medical oncologist was able to assess Blue later that same day.

Within a week, the CT scan and consult with a radiation oncologist were done, and within two weeks of the initial trip to my regular vet, he began the first treatment. About 48 hours after his treatment was completed, he was back to bounding around the park and chasing squirrels in the backyard. He had no side effects other than temporarily needing drops in his eye, which was dry. There was a lump on his face where the cancer mangled some bone, but he’s on the doggy version of ibuprofen and showed no signs of discomfort.

The little stinker even figured out that begging for treats now works for him every time.

What was the cost at that point?

I bought Blue’s health plan individually, when he was a year old. (An increasing number of clients, according to PetCure, get pet insurance through their jobs, just like human health insurance.) During his 12 years of life, I’ve paid about $9,000 in insurance premiums. The policy paid out more than $10,000 for his initial cancer treatment, in addition to other reimbursements for smaller vet bills over the years. I covered a little more than $4,500 in deductibles and co-pays from my personal savings, because I set up the insurance with a 70 percent reimbursement rate, to keep the annual premiums down.

Of course, if a dog never has an expensive diagnosis, the math goes the other way. My other dog has the same policy. So far with her, I’ve paid more for insurance than I’ve used. And it’s typical insurance — I had to fight for days to get one of Blue’s claims paid in full. Even so, I’m glad I have it. I’ll never have another dog without it again.

“Literally every client we see would benefit from it,” Chiswick says. “It’s the same cost-benefit analysis as in human medicine. You may be throwing money away, or it may save you thousands of dollars.”

According to the North American Pet Health Insurance Association, as of May 2022, Blue was among only 4.41 million insured pets in all of North America. In the United States, it’s mostly dog owners with these policies, but we represent a tiny fraction of the 69 million U.S. households with a dog.

Even so, the association says, the pet insurance marketplace increased 27.7 percent in the past year. Based on my conversations with experts as well as with Blue’s veterinary team, a lot of the people buying these policies are like me: We’ve been hit with a big vet bill in the past.

More important to me was that Blue was still covered if he survived long enough to become eligible for another round of stereotactic radiation. And yes, that was an “if.”

Even with $15,000 spent on his treatment, the projected survival time is only six to 18 months. The doctors warned me that Blue will probably be at the lower end of that range because his type of cancer is the squamous cell variety. It’s an aggressive type that fights back. A second round of stereotactic radiation is only recommended after six months and would probably buy only about half as much time as the first round.

In other words, if Blue made it to mid-October, I would have the option to go through all of this again, to maybe help him live through Christmas.

When Blue was first diagnosed, every friend with pets who I asked for advice said they’d do whatever it took to try to save their pet.

One, whose teenager is battling cancer and spends almost all her time quarantined at home with the family dog, said she’d go into debt to save that dog’s life right now.

Another, whose father recently completed radiation therapy for eye cancer, said he wouldn’t even hesitate to try to save his two mutts.

A cat-owning friend who survived Stage 3 B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma said that she, too, would proceed in Blue’s case.

A woman who works at the salon where I get haircuts told me she once spent $15,000 for a dog’s surgery, without pet insurance, and would do so again without question.

As pet parents go, I’m exceedingly common — and part smart, part lucky — to be in a position where I could actually do whatever it took for my dog to get the best available treatment.

Larisa Love, director of clinical communications at PetCure, says her team hears the same thing every day from callers to the helpline they run.

“They say it constantly,” Love told me. “We hear about a husband whose wife just died of cancer, and this was her dog, and he’s going to do everything he can to save this dog. It’s a full-circle family member. Clients who have been through cancer say their dog or cat got them through it, and they say now, they’re going to get their pet through it.”

Sadly, in Blue’s case, his tumor came roaring back in late June. Another $2,000 CT scan (covered by insurance) showed that the cancer would still overtake him even if we did a “radiation boost” and added chemotherapy.

And so as I write this, we don’t have much time left.

He has been comfortable, and on pain meds, and I’m at least comforted that I did everything possible for him. We gained another two to three months of walks in the park, swims in the river and snuggles in bed.

If I had to do it over again, I would do the same thing.

I’d pay double.

Kim Kavin wrote about Blue in her 2012 book “Little Boy Blue: A Puppy’s Rescue From Death Row and His Owner’s Journey for Truth.”

Review•

News•

News•